BidWeek, Reporting from Toronto, Canada – When International Olympic Committee (IOC) President Thomas Bach was elected based on his proposed Olympic Agenda 2020 platform – the proposed roadmap for the Olympic movement meant something.

“Agenda 2020” had favorable connotations, exuding feelings of change, of hope and a new future for the Olympic Games that previously seemed to be headed for a downward spiral. Now, not so much. The utterance of “Agenda 2020” is often met with eye-rolls and general frustration.

Perhaps it was early, but the new roadmap seemed a bit off-course one year ago on July 31 when Beijing was elected over Almaty, Kazakhstan to host the 2022 Olympic Winter Games. More on that later.

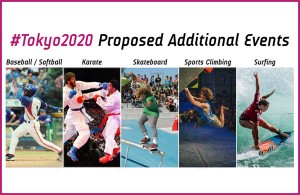

Yet next Wednesday Olympic Agenda 2020 will likely get a rare win – at the IOC Session in Rio members are expected to rubber-stamp a proposal by Tokyo 2020 to add five new sports – karate, skateboarding, sport climbing, surfing and baseball/softball – to its Summer Games program. This was made possible by recommendation 10 of the set of sweeping changes approved by IOC members in Monaco in late 2014.

After his election, Bach developed a commonly heard catchphrase, the all-but-trademarked “getting the couch potatoes off the couch” remark that illustrated his goal to get youth back into sport. Made possible by Agenda 2020, Tokyo and the IOC can now embrace more youthful sports.

Coercing the Pokémon GO generation from throwing virtual Poké Balls in an augmented-reality arena to throwing real baseballs on a non-augmented really real field will be no easy task – but it’s a way forward when it seemed like modernization of the core Olympic sports would take another millennium to achieve. If they can peel their eyes away from their screens by 2020 today’s youth might actually be inspired by more contemporary adrenaline-filled sports like skateboarding, surfing and climbing.

Another slow but possible future win is the proposed Olympic channel that on August 21, it was announced last Wednesday, will launch onto a mobile device near you. The app, conveniently located near your Pokémon GO launch button, will allow you to be inspired by “original programming, live sports events, news and highlights.”

You can watch it from your… couch.

This one still needs more time and work.

The rest are mostly messy misses.

Two recommendations from the 2014 document promised the protection of clean athletes. Sure, the IOC looked back – as far back as 2008 to identify cheats using newer, more comprehensive technology supported by a new $10 million (all currencies in USD) fund. And yes, it was discovered that, with numerous new positive tests, doping was still as rampant as ever. But do clean athletes now feel better protected by the IOC?

Thomas Bach has often taken a stance that the IOC will have “zero tolerance” for drug cheats.

Then, with the McLaren Report into Sochi 2014 cover-ups and the alleged conspiracy of state-sponsored doping by Russia – Bach and the IOC pushed the decision regarding tolerance to the International Sport Federations (IF’s). To be clear, the IOC Executive Board refused to make a decision between a blanket ban of Russian athletes at the Rio Games, or to judge each athlete based on their own culpability. It instead simply passed the buck.

Denying ownership of the problem is not quite the bold vision and leadership promised by Bach and Agenda 2020.

Of course there are specific details in the Olympic Charter regarding roles and responsibilities and the relationship between the IOC, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA), the IF’s and other key stakeholders with respect to athlete qualification – and it’s not a simple equation. Add to that the basic rule-of-law and perhaps Bach, technically, got it right.

But the optics on this issue were horrendous, and that means everything as the IOC struggles to gain back the trust of athletes, spectators and stakeholders.

On doping, the Agenda 2020 context document said “Despite progress, all stakeholders agree that doping in sport is still a significant challenge and accept that simply doing more of the same is unlikely to improve protection of the clean athletes. Novel approaches are therefore needed from all stakeholders.”

The IOC handling of the McLaren Report seemed like more of the same.

And that’s where Agenda 2020 blows up. The recommendations generally looked correct. The execution of the proposals are either underway, and in some cases complete. But the results – they are a mess.

Now to the bidding process. The proposals and changes were numerous but summarized by three main categories below, listed in reverse order for effect.

Recommendation 3: Reduce the cost of bidding

Sure – cut travel, consolidate presentation costs, and reduce printing and shipping costs with electronic bid books – that’ll save on a bit of overhead. But with current 2024 Olympic bid budgets reaching at least $60 million and more likely beyond, are the bids themselves really that cost sensitive? And with Games organizing committee budgets starting at $2 billion, what will saving a few dollars now mean if your goal is to actually win?

I’m not sure that any of the current 2024 bids among Budapest, Los Angeles, Paris and Rome jumped into the race based on a discounting of sunk costs.

Recommendation 2: Evaluate bid cities by assessing key opportunities and risks

Wait, what? Shouldn’t this always have been?

Nothing really changes on this one, it’s all about optics – especially when marketing a bid to the domestic audience. It cleans up the language around legacy and sustainability, it outlines the need to differentiate between operating costs and capital infrastructure investment (in an effort to make the fabled $51 billion Sochi 2014 price tag go away, forever) and it reminds that the Games are all about athletes and Olympism.

Basically, it’s a marketing plan template directed at would-be host city taxpayers.

Is it working?

Just ask constituents in Boston and Hamburg – both cities last year rallied against a 2024 bid based on costs and risks. Rome is on the brink of failure for the same reason.

Recommendation 1: Shape the bidding process as an invitation

This recommendation represented a return to common sense in an effort to put a human face on the Olympic bid process. Cities would be invited to bid; the IOC and candidate would work together constructively and in synergy to develop the best possible projects; the IOC would make the host city contract available to the public to increase transparency and to end white elephant insanity, bids could propose that any number of sports be staged outside the host city – or country.

Makes sense. But even after the perfect project is proposed and while the Evaluation Commission is compelled to judge and report based on new flexible allowances – will the 100-or-so secret ballots cast to elect the host city reflect these changes? There doesn’t seem to be a recommendation to change the culture of the voting group, one that often favors bids that can further personal agendas or those of connected sport federations or national Olympic committees.

Consider the bid for the 2022 Olympic Winter Games that was concluded exactly one year ago in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia – almost a year after Agenda 2020 was launched. Evaluators published a final report that showed many venues in Almaty complete, and in an ideal winter climate. In the same report Beijing was represented as needing some key venues, including most ski facilities, built for the Games – and in Games-time photographs there was no snow visible on the slopes.

Additionally, a new high-speed rail link is required to connect the main Beijing Games hub to the proposed ski venues now a 3-hour drive away. And in a bizarre reverse-transparency twist afforded by a new line item in Agenda 2020, Chinese officials weren’t required to disclose the plans or costs for the mega rail project.

“The high speed railway is just a part of … a big project not related to the Olympic Games,” Evaluation Commission Chair Alexander Zhukov told me in Beijing, indicating that the rail costs were not even discussed.

You can’t tell me that the most critical transport link that could make or break the Games is not considered a risk worth discussing and is “not related.”

More likely, it’s part of the overall optics effort to downplay infrastructure costs and risks in order to keep the bid politically friendly. During the four day Evaluation Commission visit, Olympic journalists along with myself interrogated both Beijing 2024 representatives as well as those with the IOC for any hint at what the rail line might cost, and for evidence that the project was, as described, already part of the overall national rail plan. It was to no avail.

It doesn’t really seem to matter now, but the Beijing bid won by a vote of 44-40 making it the first city to play host to both the Summer and Winter Games. Agenda 2020? Not much of an impact.

We also noticed that estimates for some other capital infrastructure costs for both bids, such as housing projects to be used for the Olympic villages, were no longer documented as they had been in past bid campaigns. So while the IOC and bid cities effectively differentiated operational and capital costs as they had promised in recommendation 2, they also made some of the riskier capital costs seem to disappear by classifying them as existing projects – whether they were or not.

It’s a new strategy to avoid any future $51 billion Sochi 2014 price tag debacle. It’s also a diminished level of transparency leading to a false risk assessment.

Is Agenda 2020 leading to clarifications, or falsifications?

[Continues Below][posts_carousel query_type=”tags” tags=”BidWeek” animationloop=”true” hide_excerpt=”true” hide_meta=”true”]

Now Budapest, Los Angeles, Paris and Rome are locked in a battle to host the 2024 Games and they are using Agenda 2020 for guidance and operating on a new set of bid processes first outlined in Kuala Lumpur one year ago.

Baku and Doha were reportedly vetted in the “invitation stage” and opted to bid instead for a future Games, for unreported reasons. Hamburg dropped plans after losing a binding referendum.

Will the four remaining bids, or the IOC benefit from Agenda 2020?

It depends how the 100ish IOC member votes are cast September 13, 2017 in Lima, Peru.

It depends how the 100ish IOC member votes are cast September 13, 2017 in Lima, Peru.

They may choose the bid with the lowest cost and least risk for taxpayers – the city that stands to benefit most from the Games. Or they might vote for the concept that delivers more for the athletes, the Olympic movement or for whatever other organization the member feels connected with.

But the chances are they won’t correlate three volumes of bid books and an evaluation report that is seldom read through – with the framework of Agenda 2020. They’re IOC members, they’ve earned the right to make up their own minds for their own reasons. So then, while a regional bid using existing and perhaps not state-of-the-art venues can be proposed, will it stand a chance – or is it destined to be defeated by a more impressive, costlier concept?

They’ll want to know that answer in Australia.

This week a group in South-East Queensland released a study and plan to pursue a regional bid for a Brisbane 2028 Olympic Games. The plan, leveraging the rhetoric in Agenda 2020, involves eleven mayors that need to throw support behind the project.

Eleven mayors? And that’s LESS risk? Note to Australian officials: Agenda 2020 has documented theoretical acceptance of a widespread regional bid plan, but IOC members have yet to demonstrate that they’ll embrace such a concept by casting ballots accordingly. Do a study on that before you go all in.

As the Rio Games are set to launch, Bach is under fire and confidence in Agenda 2020 has eroded.

Agenda 2020 delivered words. The words delivered action. Now what we need are results, and it’s up to Bach and the Executive Board to steer the Olympic movement back in the right direction.